It's easy to forget the formalities of earlier eras in our increasingly casual American culture. The rules of civility were far more rigid in Victorian times, so it's fascinating to study Elizabeth Gaskell's use of first names and surnames to indicate formality, familiarity, and feeling in North and South.

The first word of the book is "Edith!" and Gaskell begins by throwing the reader into the midst of a private scene between two young cousins on the cusp of womanhood. The familiarity between Margaret and Edith is drawn to highlight their differing stations and characters as well as to indicate their close relationship. Edith and Margaret are family—practically sisters, considering the amount of time they've lived together in the Harley Street house over the past nine years.

Brothers and sisters, of course, refer to and address their siblings by their first names. Mrs. Hale speaks of Aunt Shaw as "Anna." Fanny explains who Mr. Hale is to a dinner guest by saying, "My brother John goes to him twice a week..." And in a rare display of casual familiarity, John calls his sister "Fan" as he chides her for always having some kind of ailment.

The foundation for all traditional family relations is marriage, and the relationship between husband and wife is unique. A Victorian wife would customarily speak of her husband in a formal manner in front of others. The use of his first name would be a private matter between them. We get a peek of the sweet intimacy between Margaret's parents when Mrs. Hale rushes into her husband's arms saying, "Oh! Richard, Richard, you should have told me sooner!" on the day Margaret breaks the news of her father's decision. Mr. Hale, in turn, uses his wife's first name, Maria, in moments of emotional anguish—when he's feeling terribly guilty about her suffering.

Margaret, as the young unmarried heroine of the story, is almost always referred to and directly addressed by her first name. It's especially interesting to note the exchange between Margaret and a male friend of the family: Mr. Henry Lennox. From the very first chapter we see that while Henry is free to speak to Margaret by her first name, when Margaret thinks or refers to him it is always as "Mr. Lennox." Edith, however, as Henry's sister-in-law, is free to addresses him by his first name, which she does several times in the concluding chapters. (Side note: Gaskell never has Margaret directly address Henry by his name at all—either with "Mr. Lennox" or "Henry"—throughout the entire book.)

The BBC adaptation brilliantly creates a distinction of familiarity between Margaret and Henry by having Margaret call Henry by his first name. In the scene at the Great Exhibition, just after John and Margaret have separated themselves from the crowd to argue about how well they assume to know each other, Henry arrives on the spot. Margaret is uncomfortably forced to provide some kind of introduction:

Henry ... do you know Mr. Thornton?

The effect of this utterance is staggering on John Thornton. The seething look of jealousy John gives Henry can hardly be disguised. There's no doubt that John has bitterly noted that while the strange gentleman from London has the honor of being called by his first name, he remains a more distant "Mr. Thornton" to Margaret. The distinction is acute, and the way he glares at the competition throughout their exchange is categorically lethal.

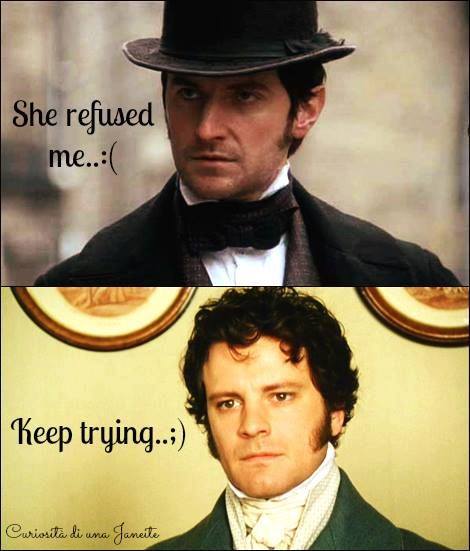

The BBC's John Thornton stares down Henry Lennox.

Poor John always seems relegated to the status of an outsider in many respects: he is the foreign northerner; he is a tradesman--a notch below a gentleman's family; he is the unrefined man who comes to Mr. Hale to continue the education he was forced to abandon; he is the busy workingman who doesn't have the time for leisure or social finesse. He feels these distinctions that separate him from Margaret and make him feel unworthy of her. His longing to be a part of her inner circle and his envy toward those who are in it is palpable throughout the book. To her, he suspects, he will always be "Mr. Thornton."

Because he has no close relationship with her, he refers to her as "Miss Hale" with his mother, and in addressing Margaret herself. Even when he comes to declare his love for her the day after the riot--even in the heat of passion of revealing his feelings--he still controls himself enough to address her as "Miss Hale."

Although the bursting longing to have a special bond with her is contained outwardly in the formalities required of the time, his private thoughts and exclamations are thronged with her first name:

Oh, my Margaret - my Margaret! no one can tell what you are to me! Dead - cold as you lie there, you are the only woman I ever loved! Oh, Margaret - Margaret!

and later:

Oh! Margaret, could you not have loved me? I am but uncouth and hard, but I would never have led you into any falsehood for me.

The relationship between Thornton and Margaret is strained from the very outset. Margaret's initial judgmental assumptions about his class and position keep her haughtily distanced from him, all while he strives to make himself understood. After she finally wakens to appreciate his true character, the strain between them takes a new turn with the compounded misunderstandings concerning Frederick and her lie.

When Margaret moves to London, the division between them remains unresolved. Both have resigned themselves to the assumption that they will live their lives alone. When Mr. Thornton comes to dinner in London, the tension of fervent attraction between them is renewed, although they both try hard to hide their tumultuous feelings. Margaret cannot help blushing in his presence; Thornton cannot help but look to Margaret for a hint of approval.

The BBC's version of the tender final scene.

How tremendous is the impact, then, of what takes place a few days later when these two silent sufferers finally find themselves alone together in Aunt Shaw's back drawing room. Both begin their conversation with all the awkwardness of formality as Margaret mentions Mr. Lennox, and Mr. Thornton interrupts to say something of his hardships. To which, Margaret stammeringly answers with her business proposal.

Silence ensues for a moment while Margaret shuffles papers nervously until:

...her very heart-pulse was arrested by the tone in which Mr. Thornton spoke. His voice was hoarse, and trembling with tender passion, as he said: -

"Margaret!"

And thus, with the utterance of one word--her name--all formality between them is dropped; the atmosphere of the room entirely changes. He calls to her as an intimate equal, begging her to reply in kind.

And she does. Not with his name, but with a very tender physical gesture--laying her face on his shoulder--which answers his unspoken question and puts an end to the tortuous separation between them forever.