Did you ever notice how the leading male characters in North and South all quit or lose their jobs? Mr. Hale, Nicholas Higgins, and John Thornton. Even more striking is the realization that they all do so based on principle.

The entire plot of the story gets its initial push from Mr. Hale's decision to leave his life vocation. This is a tremendously serious and weighty decision in an era when your profession constituted your identity and your social status. I know many condemn Margaret's father for the way he handled his family in relation to this life-altering choice, but the choice itself is one of courage and personal integrity. Because he could not in truth uphold all the doctrines of the Church, Mr. Hale could not in good conscience continue to play the part of a leader of the Church. He was unwilling to fake it just to keep hold of his living.

Mr. Bell admires him for his hard decision and tells him so just hours before Hale passes away:

[God] gave you strength to do what your conscience told you was right; and I don't see that we need any higher or holier strength than that; or wisdom either. I know I have not that much; and yet men set me down in their fool's books as a wise man; an independent character; strong-minded, and all that cant. The veriest idiot who obeys his own simple law of right, if it be but in wiping his shoes on a door-mat, is wiser and stronger than I. But what gulls men are!

Henry, who represents the mediocre mindset of traditional society, doesn't see why Mr. Hale couldn't have just swallowed his doubts and kept his position. He's rather perplexed that anyone should inconvenience themselves and lose their money and status over a minor moral issue. He apparently sees nothing wrong with playing the game of appearances.

...there was no call upon Mr. Hale to do what he did, relinquish the living, and throw himself and his family on the tender mercies of private teaching in a manufacturing town; the bishop had offered him another living, it is true, but if he had come to certain doubts, he could have remained where he was, and so had no occasion to resign.

If income was any barrier to acting on principle, Nicholas Higgins would have the strongest reason to avoid leaving his livelihood. With two daughters to care for, and one of them gravely ill, it's more than inconvenient for him to quit his job. As one of the Union leaders, he helps organize the strike. Here he's not only giving up his own job, he's actively involved in pressing other mill workers to quit their work! And his reasons are noble, if his methods are less than savory. He is moved to act in defiance of the perceived injustice and indifference of the masters to the struggling lower class.

Higgins holds to his principles, even after taking on Boucher's children. He refuses to go back to work at any mill that refuses to allow the workers to contribute to the Union. Clearly, Higgins has the mettle to take a stand for what he believes is vital, despite the personal cost.

John Thornton's case is a bit different. He doesn't quit his work, but he does make a moral decision that precludes him from the chance of recovering his business. He refuses to join the speculation that could save his mill. He will not risk the money that rightfully belongs to his creditors and the workers. It's a heartrending decision that only a nobler man could make. His own mother is inclined to take the risk to avoid failure:

'I know now that no man will suffer by me. That was my anxiety.'

'But how do you stand? Shall you -- will it be a failure?' her steady voice trembling in an unwonted manner.

'Not a failure. I must give up business, but I pay all men. I might redeem myself -- I am sorely tempted--'

'How/ Oh, John! keep up your name -- try all risks for that. How redeem it?'

'By a speculation offered to me, full of risk; but, if successful, placing me high above water mark, so that no one need ever know the strait I am in. Still, if it fails.... As I stand now, my creditors' money is safe...it is my creditors' money that I should risk.'

'But if it succeeded, they need never know. Is it so desperate a speculation? I am sure it is not, or you would never have though of it. If it succeeded--'

'I should be a rich man, and my peace of conscience would be gone!'

Note that John's concept of failure is quite different form his mother's. Hannah, more like Henry, appears concerned with the outward appearances, whereas John considers it a failure to act against his moral judgement. He knew it that if he risked saving his position, it would always rankle him to know what he had gambled. He would lose a portion of his self-esteem and honesty. And so he felt he had no choice but to close the mill.

For Thornton and for Higgins (and to a lesser degree for Mr. Hale), the decision to quit involved not only an evaluation of the consequences for oneself, but for the responsibility of one's obligations to the community of people you are involved with.

In each of these cases, it's crucial to the ongoing plot that these three characters make dramatic decisions to quit their jobs. But more importantly, Gaskell is clearly emphasizing that the courage and moral integrity of these men is a cut above the common breed. It takes guts to quit your work in any era, but more so in an age when your role in society -- your very identity as a man -- is dependent on the working position in which you are engaged in. Stripped of their outward vocation, all three of these men must define themselves on a higher order. And they do. These men are moved and strengthened by their inner convictions of what is right, and their duty to others. They cannot act contrary to what their conscience dictates. Their sense of identity rests on something far more important and substantial than a job. Their true vocation is to think and act according to their individual convictions of honesty and justice. There are men because of how they form themselves according to their highest ideals, not because they perform certain ascribed functions for compensation.

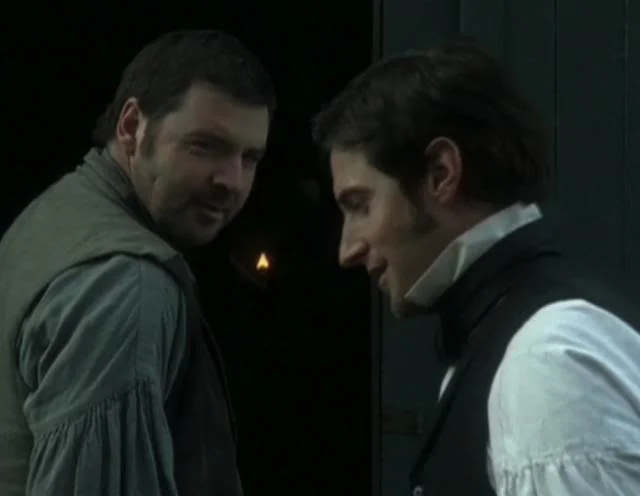

Is it any wonder that these three men are friends with one another? There's a wonderful sense of warm camaraderie in the scenes where any two of these men meet in friendship and care.

Photos from the BBC mini-series North & South (2004)

I love the way Gaskell forces these men to step out of the traditional evaluations of manhood based on social position and economic structures. She always compels the reader to look under the surface for the real individual - not defined by vocation, wealth, or social status. As always, Gaskell is pointing out our highest calling -- each of us -- as human beings attempting to live up to our best selves for our own and humanity's good.

These quitters are winners in my book.